European cities — and municipalities from developed countries, more widely — have at their disposal a plethora of opportunities to network, learn from one another, and share their experience and views at the global level. Which place, though, for the cities from the Global South, in the field of city diplomacy, once we leave the capital or the charismatic cities out? This is one of the questions the ASToN program tried to answer, looking at how African cities can be in the driver’s seat in both their digital transition and international action by joining a group of peers for three years.

By Simina Lazar

African cities are among the youngest and fastest growing in the world. While numbers vary, Lagos (Nigeria) alone is said to welcome 4000 new persons every day who are looking for better living conditions in the metropolis. Like everywhere else, this demographic increase puts enormous pressure on the infrastructure, housing, and job opportunities available, not to mention on the public services and the development of the informal market. At the same time, this presents an opportunity to do things differently, tap into Africa’s innovation and creativity, and link it with potential technology offerings by bringing people together to discuss solutions and ways forward.

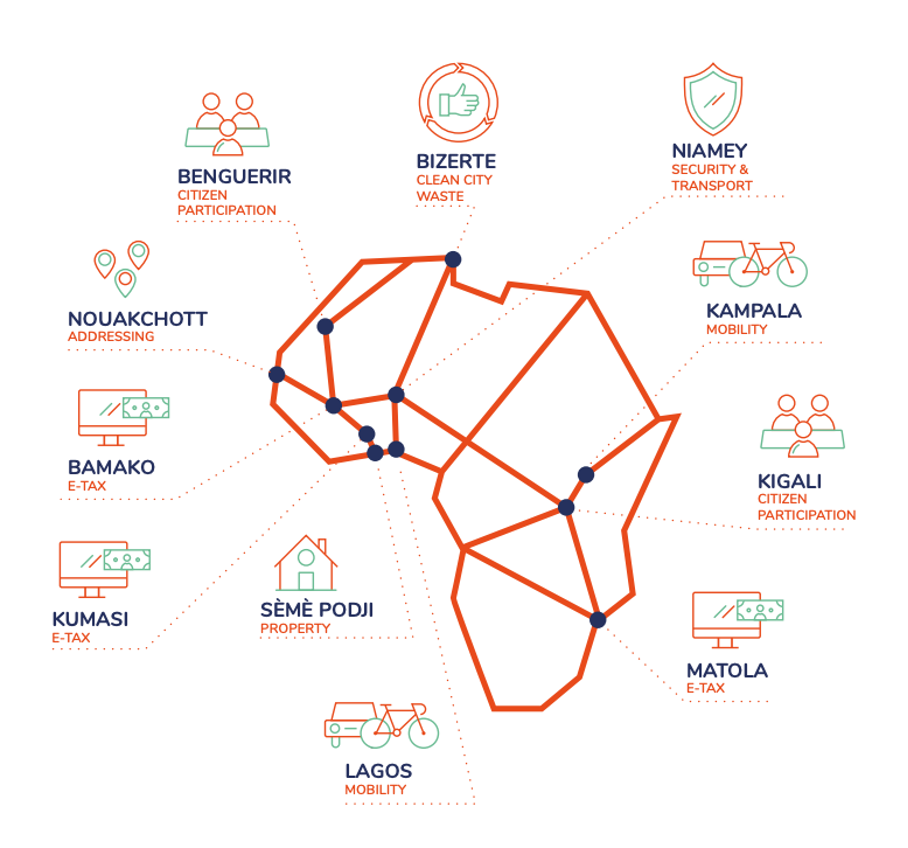

Despite their energy, innovation, and creativity, African cities are not yet fully present at the table of global discussions. For example, the 2022 UN-Habitat Global Review of Smart City Governance Practice only saw 14 African out of 250 cities replying to the survey. So how can African cities make their voices heard beyond their borders when internet cuts, staff shortages or dealing with emergencies is their daily routine? While continental, ambitious initiatives are still rare and financial resources are often scarce, African city leaders can bring their unique perspectives and challenges to the international table of discussions. Here are the main lessons from the ASToN (African Smart Towns Network) program that, from 2019 to 2022, assembled 11 African cities on an experimental learning journey. The program was financed by the French Development Agency (AFD) and used URBACT methods and tools.

Building a community of practitioners across 11 African countries…

ASToN focused on the unique digital challenges brought by the cities and on the humans that represented them. By testing, learning, and iterating, a program journey was designed that was adaptive and responsive to the needs of cities. It offered a regular rhythm and balance, bringing in technical expertise and city experience. Fully aware that our initiative is a one-off, our ambition was also to create a community of people that would outlive the program.

While we were aware that the digital maturity of both institutions and the territory was variable across the network, little did we know about the cities’ previous exposure to international programs or their representatives’ participation in somewhat similar initiatives. Here again, we found a gradient of situations, from Kampala (Uganda) or Niamey (Niger) leaders, used to taking the floor in international conferences and gatherings, to Sèmè Podji (Benin) or Matola (Mozambique) representatives who were joining an international group of peers for the first time. The challenges they were confronted with are similar to many other city leaders around the world: initiatives like ours came on top of already very heavy workloads, internal procedures and hierarchy were often incompatible with the lean approach our program required, and their administrations often faced important turnovers. So, how do you build a network of peers in such a context, and more importantly, how do you make it last beyond the program’s life?

Through ASToN, we tried as much as possible to create a community and sense of collective identity and belonging between participating cities. Our assumption was that these relationships would outlive the network and spark more opportunities than we could imagine. The community can boost any other types of support that might be offered by program activities, as it allows people to take the lead and ask for what they need from one another directly[1]. Making change and doing things in new ways in a city authority can be hard. We thus designed settings that allowed city representatives to provide their counterparts with support and guidance based on their deep technical expertise and previous experiences. With turbulences like changing politics or external shocks, we also realized there could be a strong sense of peer support for when progress is hard – a feeling of being ‘in it together.’

The Agile approach that was proposed to cities to develop their digital solutions at the local level was also used as a wider framework for network activities. From the start, our commitment was to keep things moving while also being ready to close things down when needed. In doing this, we built coalitions of relevant partners who could support and inspire participating cities by organizing small thematic groups around mobility, e-tax, or land management, some of the main sub-themes of the network. We were also mindful of the fact that different cities were moving at different paces. Unforeseen shocks like the pandemics, social movements such as the 2020 Lagos #endSARS riots, or natural disasters such as the flooding that hit Niamey in early 2021 meant that some cities were absent from group activities for certain periods. Nonetheless, when able to do so, they all came back, proving how relevant the network was for them.

…and providing a platform

A key priority for ASToN from the start was communication, and it became crucial when the pandemic hit. By developing several strategic partnerships with Civic Tech Innovation Network, the UN-Habitat People-Centered Smart Cities program, or Bloomberg’s network of Chief Innovation Officers, ASToN city leaders participated in several high-level discussions. Several ASToN cities, like Bizerte (Tunisia) or Kumasi (Ghana), continue to be invited every year to such events as the Smart City Expo, speaking out not just for themselves but for their fellow African partners. Sèmè Podji joined in 2023, together with several French local authorities, a cooperation program led by PFVT focusing on digital transitions, directly contributing to the UN-Habitat Smart Cities resolution. For example, some city leaders from Nouakchott (Mauritania) decided to take on more formal training by enrolling in Master’s degrees in urban planning, smart cities, or digital transitions rolled out by African Universities.

We are also aware that the space for cooperation and exchange is closing in some parts of the world, and the possibility that some cities will have to exchange and learn beyond their borders is no longer possible today. This is the case for Niamey or Bamako (Mali), where different political visions, as well as endemic electricity shortages, make impossible the kind of work an international program requires.

What money can and cannot buy

What about the lessons learned from investing nearly 3M€ in a one-off program like ASToN? Despite the challenges encountered along the way, 9 out of the 11 cities ran pilot phases, and all of them designed digital solutions for the challenges they had identified. We organized several pitching sessions where cities presented their solutions to potential partners and investors. Nonetheless, the opportunities they were offered remained limited in comparison with what is possible for their European counterparts. If some cities advanced in developing their solutions, like Benguerir’s (Morocco) app or Kampala’s mobility solution, this was done through internal funding. For others, like Bizerte, ASToN proved to be the stepping-stone for the city to join several national initiatives, acting as a pilot case for implementing a digital one-stop shop for citizens or developing an online Services Kiosque. These are, of course, important spillover effects from an experimental initiative like ours. However, they also show the extent to which African cities are still on the receiving end, integrating investor or donor programs coming from above rather than negotiating international finance to push their strategies ahead.

The Blueprint for Running a City-to-City Cooperation Program contains all the lessons learned from designing and running ASToN, from the practical to the more strategic. It also presents tools and tips for carefully designing the onboarding method or the support and grant funding mechanism, in addition to some other points that I raised in this article.

For policymakers who are considering building such initiatives, there is one more thing I can add today, more than a year after the program ended. ASToN’s unique proposition also proved its weakness. Back in 2019, we were the only network dedicated exclusively to African cities, providing tools and resources for both local activities and network interaction. Thinking in detail about what comes after, which are the exit strategies both for cities and the program as a whole, must be at the core of such experimental programs to build lasting results. While the community continues to exist and bilateral relations grow, more resources and support are needed for African cities to bring their voice to those discussion tables where what tomorrow is made of will be decided.

[1] In the Secretariat, we would do a victory dance every time we heard about cities working together or asking for advice from one another, outside ASToN’s official communication channels.

Header image: field visit during the Kigali all-partner meeting in November 2021.